Leaving genteel Inverness behind with the waters of the Moray Firth lapping quietly at its feet, the coach chugs up into the Cairngorms.

This is Britain’s largest National Park, though the mountains that rear up on either side seem to admonish the idea that they need anyone’s protection. Wind-worn, heathered slopes rise toward boulder-strewn plateaus and high, rocky outcrops—like the granite pulpits of a vast and fearful god.

The weather up here can be treacherous but, on this last day of the meteorological summer, the blank sky maintains its innocence.

Journeys Back in Time

I’m on my way to my first housesitting gig. This part of the plan came up when I was looking for ways to avoid taking a crummy job that would cover my rent. I wanted to be free to write full-time and I didn’t want to wear out my welcome with family and friends.

The solution turned out to be online marketplaces where pet owners connect with tourists and travelers. It’s like Airbnb in the early days, before the tsunami of faceless investment properties, when you stayed in people’s actual homes. Except that instead of paying cash, visitors take care of the resident animals, plants, and maybe gardens or even farms.

I found my pick of comfortable living arrangements on a British housesitting site (I also joined an international one) and now I’m headed to Broughty Ferry, a small town right next to Dundee, the city where I spent the earliest years of my life.

I made this journey many times as a child when my younger brother and I would drive south with our mother to shop for new clothes and a better selection of books than was available in the North. We stayed with Mum’s friend from teacher training college and David and I, unfamiliar with city streets, would take off on our own adventures while the grown-ups had boring conversations about teaching and schools.

As the bus crests the Drumochter Pass, 460 m (1508 ft) above sea level, I see the gravelly pull-off where one winter, fifty years ago, we stopped to sweep a million tiny cubes of shattered windscreen out of our clothes and hair.

The 18th century military road was receiving its first major rebuild and the vehicle ahead of us must have kicked up a stray chip. The forlorn service station a few miles down the road sold us a temporary windshield made of ribbed plastic and we carried on, David and I huddled in the back seat. Even wrapped in coats and hats with scarves around our faces, we arrived in Broughty Ferry brittle with cold.

Shattered

After the wildness of the Highlands, Scotland’s midriff is a contrast of gently undulating farmland and broad, well-mannered rivers. The most delicious raspberries and strawberries are grown here. Dairy herds amble the green fields beyond the great rolls of straw baled ready for winter feed.

Bus stations are rarely in the scenic part of town but, as the coach pulls into Dundee, I am shocked by the ugliness and dereliction. The traditional manufacturing and heavy engineering industries that had been mainstays of the city’s economy began closing or moving away before I was born. The decades of decline since then have only added to the sense of despair that clings like soot to the Victorian stone buildings of the old town.

It’s worse in surrounding neighborhoods. Boarded-up cinemas and bingo halls sprout moss, grasses, and even small shrubs from what were once fine Art Deco facades. Scotland has the highest rate of drug overdose deaths in Europe and Dundee is the firmly established epicenter.

The city center is a cheerless collection of crumbling concrete shells and I recognize almost none of the shops or businesses from the years when my family shopped here. The scene is so miserable that I think I’m about to cry when I bump against a man behind me who is balancing on two mismatched crutches. I apologize and he responds with a good-natured, “Yer aw rite, Pal”.

“Och, watch where you’re goin’, ya daftie”, says the woman beside him. It becomes clear that the rebuke isn’t meant for me when she rolls her eyes in his direction and tells me, “Yer aw rite, Hen. He’s lethal wi’ they things”.

It’s a long time since I’ve been called Hen, or Pal, and I immediately feel better. People are the heart of any place, no matter what it looks like, and the woman’s thick-throated accent reminds me of the person who was always the heart of Dundee for me.

In Safe Hands

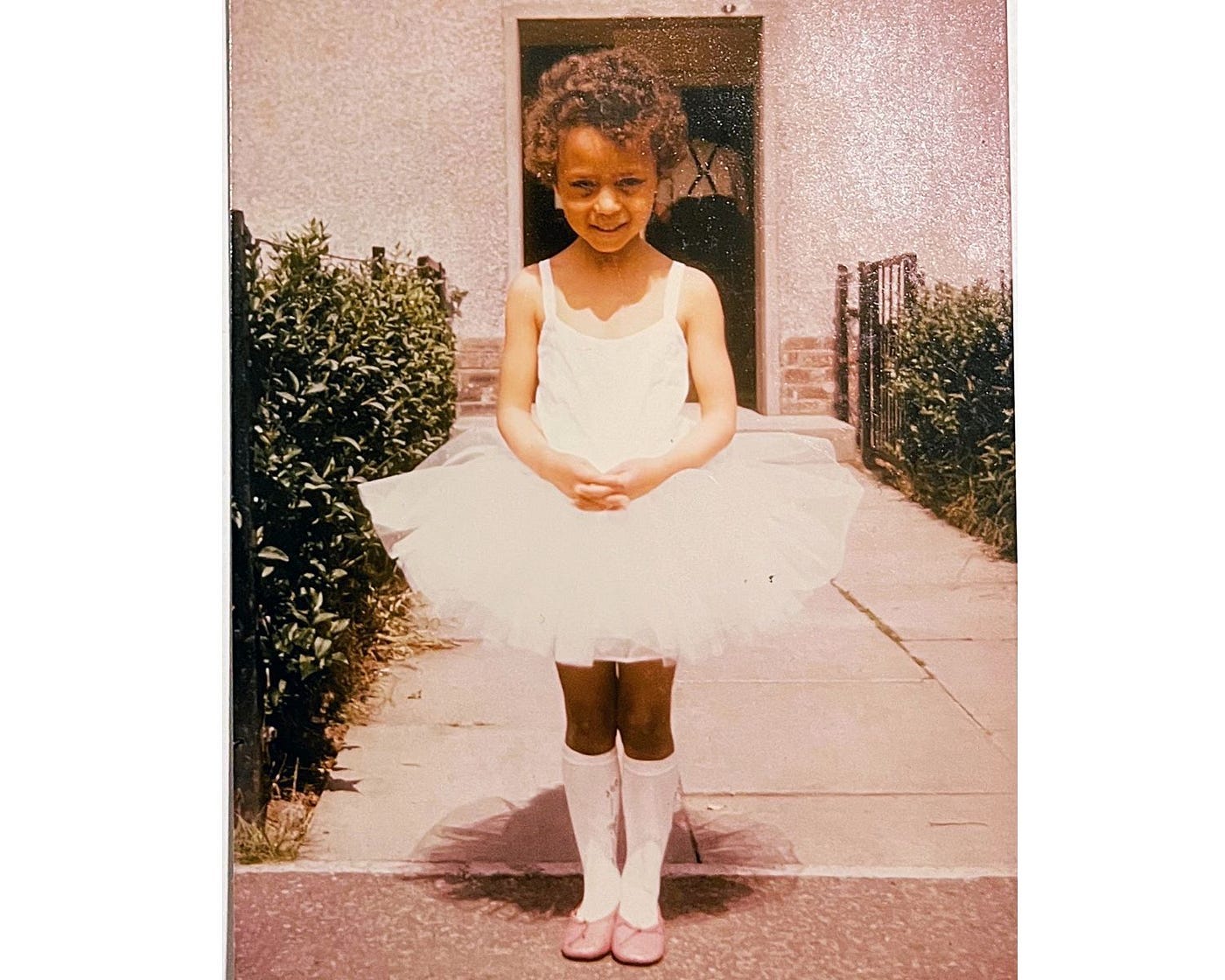

When I first spilled out into the world, an uncoiling of slippery hopefulness, the hands that caught me were Joan’s.

Joan was my mother’s best friend. They were nurses together at Dundee Royal Infirmary, the hospital where I was born and where Joan was finishing up her midwifery training. Mum was a transplant to Dundee, the camp follower of Dad’s medical career, but Joan was hometown to her core—a practical, indomitable Scot. A woman of bold words and deft action, she made sure Doctor Dad was in the delivery room to witness my birth at a time when most fathers made themselves scarce.

Joan was unmarried and lived with her parents, working-class people who had built a decent life after WWII when the city was still industrious. They lived in one of the new pre-fabs, a semi-detached bungalow with a well-tended back garden. Mr. and Mrs. S. were kindly people, always ready with a tease, a cuddle, or a bottle of pop.

I was too young but the story goes that no one was allowed into their home after midnight of December 31st until my father came to call. Scottish custom holds that good luck follows when the first person of the year to cross your threshold is a tall, dark handsome stranger—that made Dad a shoo-in for their choice of First Footer.

In the 1960s, Dundee was a city of simmering racial and sectarian tensions but it was also a port city with a centuries-old history of arrivals from around the world. While some Dundonians were hostile or fearful of our bi-racial family, Joan and her parents were unfazed and welcomed us in as their own.

Life on the Estate

We lived in a long block of tenement buildings on a council housing scheme, what Americans call the projects. Six flats, two on each floor, shared a close, the stairwell the coalman trudged up each week, heavy footfalls resounding off the painted concrete walls before the rap at the door and a grunting heave as chunks of coal tumbled into the bunker just inside.

The coalman would stand on the door mat, careful not to touch anything, wheezing black dust as Mum fetched her purse and counted out the shillings and pence into his calloused mitt.

When Mum and Dad were both on duty at the hospital, Joan came to babysit. With no children of her own and no suitors either, Joan filled our small flat with bustling warmth. I can still feel the fondness of her smile.

Sometimes, she treated us to bottles of fizzy orange from the roving lemonade lorry, or sent my older brother to the chippy for a fish supper we would all share. My parents had no money for such extravagant delights, we were a baked beans-on-toast-for-tea family.

Joan played dolls with me for hours and then let me brush her hair. She would lower her large soft body onto the sofa, home-manicure kit and Avon hand lotion at her side. She smelled of wet nylon and lily of the valley. I perched high on the back of the couch, marveling at the mountain of her, dragging bristles through her long dark hair until grease pricked and turned the thin strands slick.

Downhill Slide

Things began to change after I started preschool. Dad had a series of medical issues, each one compounding the other until he was admitted to hospital for emergency surgery. My timeline is muddled but daily life morphed itself around Dad being at the hospital, as a patient, not a doctor. Mum went to visit on Sundays but children weren’t allowed and Joan came to hold the fort.

Dad came home. Dinner dishes waited on the table as Mum wound impossibly white gauze around and around the dark secrets of his abdomen. Then he was back in hospital, sicker than ever. He was moved to a specialist unit in Edinburgh and we piled into the car each week for the 90-minute drive. While Mum visited Dad, we kids waited in the hallway amid the smell of disinfectant and old men in striped flannel pajamas.

Mum pulled extra night shifts to make ends meet and a dusty silence hung in the daylight that filtered through the curtains while she slept. My older brother had neighborhood friends now, so it was only the two youngest of us watching TV with the volume turned down, or bickering until Mum emerged from the bedroom and sent us outside in search of something to do on the sad patch of grass between the blocks of flats.

Joan’s visits became more frequent. She had furtive conversations with Mum when she got home from work, bad news and worry I wasn’t allowed to hear. Hovering around the margins of such a conversation one day, I was whining about the lack of attention I was receiving—I don’t remember what I said. But I remember Joan.

Her feet were planted squarely in front of me, hands on hips, staring me down, furious. “If no one cared about you, you’d be sitting out there in that gutter!”, she told me.

When was that? Was Dad still in hospital? Or had he already gone, trying to heal in Kenya while the bills piled up at home in Scotland?

I don’t know how old I was but in the picture I made for myself that day, I’m about five. I’m sitting on the curb outside our flat with no coat and my feet in the gutter. Behind me, the sad patch of grass is empty and, on either side, harmless parked cars loom over me. Trash clogs the grate over the drain but, for once, I don’t have a stick to poke at it. I am utterly alone and ashamed.

Dundee in the Rear View

Mum went back to school and became a teacher. We moved north across the Cairngorms to a tiny Highland village and the rhythm of our days steadied. As Dundee continued its downhill slide, Joan found love and made a happy home there.

She birthed a baby of her own and Mum labored over knitting that hung from her needles like pale blue worms. Joan’s son was asthmatic and skinny as a string bean by her telling, they never came to visit. The connection between our families gradually unspooled to the odd card at Christmas and then nothing at all.

I thought it would be fun to send Joan flowers and a thank you card on my 21st birthday but she died a few years earlier. Her parents had gone long before and so had her son, who had never quite managed to thrive.

Walking from the bus stop to the center of Dundee, successive attempts at rejuvenation peel away in well-faded ‘closing down’ signs among the brightly lit shops that offer to buy gold jewelry and electronics for cash.

I read that much of St. Mary’s parish, where we lived, has been demolished or refurbished. I don’t have the heart to go and visit but I looked on Google Earth and our tenement building is still there. I zoom in on our road and the grassy play area still looks bleak but there is no one sitting in the gutter.

Back to ‘The Ferry’

The lovely owner of the dogs I will look after picks me up and takes the old road into Broughty Ferry so I can see if I recognize it.

The Ferry grew up around its castle, as a fishing and whaling village and, presumably, the home port of a ferry. In Dundee’s heyday of ‘jute, jam, and journalism’, wealthy factory owners built sandstone villas by the sandy beaches overlooking the Firth of Tay. Those core manufacturing industries are long gone but the pretty seaside town is clearly still home to well-heeled upper management types.

We drive alongside the brand-new flood defenses that include a coastal cycle path. As the castle comes into view, I find my bearings. My eye is immediately drawn down the street where my brother, David and I would have run home to the flat where Mum and her friend may have opened the sherry, or on towards the shops and Visocchi’s where we would look at the fancy sweets in the window and discuss our chances of being given money for ice cream later.

This is the only corner of the town that feels familiar and a few days later, when I’m settled in with my two delightful Bichon housemates, I head back.

I’m surprised by the views and old buildings that don’t spark a memory more than by the ones that do. I take photographs until I realize that, since David is gone, there’s no one to send them to.

Like the ripples of stracciatella gelato folded over each other at Visocchi’s, the memories and absence are sweet and cold at the same time.

Thanks for reading and listening, I appreciate your company as I travel along.

Readers like you subscribe to Whole Stories Shortly to follow my work as I write and travel.

Upgrade to become a paid subscriber, and you help to keep the wheels turning with delights like a fish supper drenched in malt vinegar—what could be better than that?!

"When I first spilled out into the world, an uncoiling of slippery hopefulness, the hands that caught me were Joan’s." What a fantastic visual! Your writing is amazing. 🤩 Joan's story makes me a little sad. It's sad to think her whole family is gone. I hope she experienced happiness. Love your photos! You can post your photos here and we can witness them for you.

Such a heartfelt journal, thank you Beth for sharing it with us. I'm hoping there are other anchors to steady your memory like the castle in this one.. I loved the little vignettes of life with Joan while so much was swirling around you as a young child. I'm glad your mother and your whole family had such a good friend.