The Genius of Bold Beginnings

Reinventing your life calls for courage, imagination, and a little bit of magic

I have been told lately—a lot—that I’m brave.

It’s because I quit my job and decided to be a writer. Because, instead of taking up painting or pickleball when I became an empty nester, I put the family nest up for rent and set off across the ocean with no particular destination in mind.

‘Brave’ can mean a lot of things but what most people seem to mean is that I am being plucky, or reckless—foolish. Batshit crazy, maybe. They’re not entirely wrong.

The job I gave up was pleasant and respectable. I worked for a nonprofit and the salary wasn’t great but I could’ve squeaked by, could’ve done a bit of DoorDash on the side to pay for nice extras. My retired neighbor dashes; if there’s a security camera, he hobbles towards the front door like he’s a 90-year-old delivering house bricks instead of pizza—it gets a better tip. I could’ve done that.

Instead, I’ve staked my ability to pay my mortgage on a guy I’ve never met, and a family I don’t know is going to live in my home with my stuff. I have stepped off the work-to-live-to-work merry-go-round and, as some people see it, I have blown up my life.

Family Destiny

This isn’t the first time I have decamped to a far-off land to begin a new adventure. In my 60+ years, I’ve been a resident of Scotland, England, and the U.S., with other, more temporary stops along the way. I’m not cut out for ‘fitting in’ or ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ but then, my parents weren’t cut out that way either.

My father was the eldest son of his Kenyan parents. When a Scottish missionary wanted family land to build a hospital, my grandfather refused his offer of cash and instead, asked the missionary to sponsor my father’s education so that he could one day become a doctor in the hospital.

My father was sent first to Nairobi, a day’s travel to the south, and then, because colonial rule forbade high school education to non-Whites, to the windswept East Coast of Scotland. No one in the family had ever traveled so far from home and, with its inherently racist social systems, Britain would be chilly for him in more ways than one.

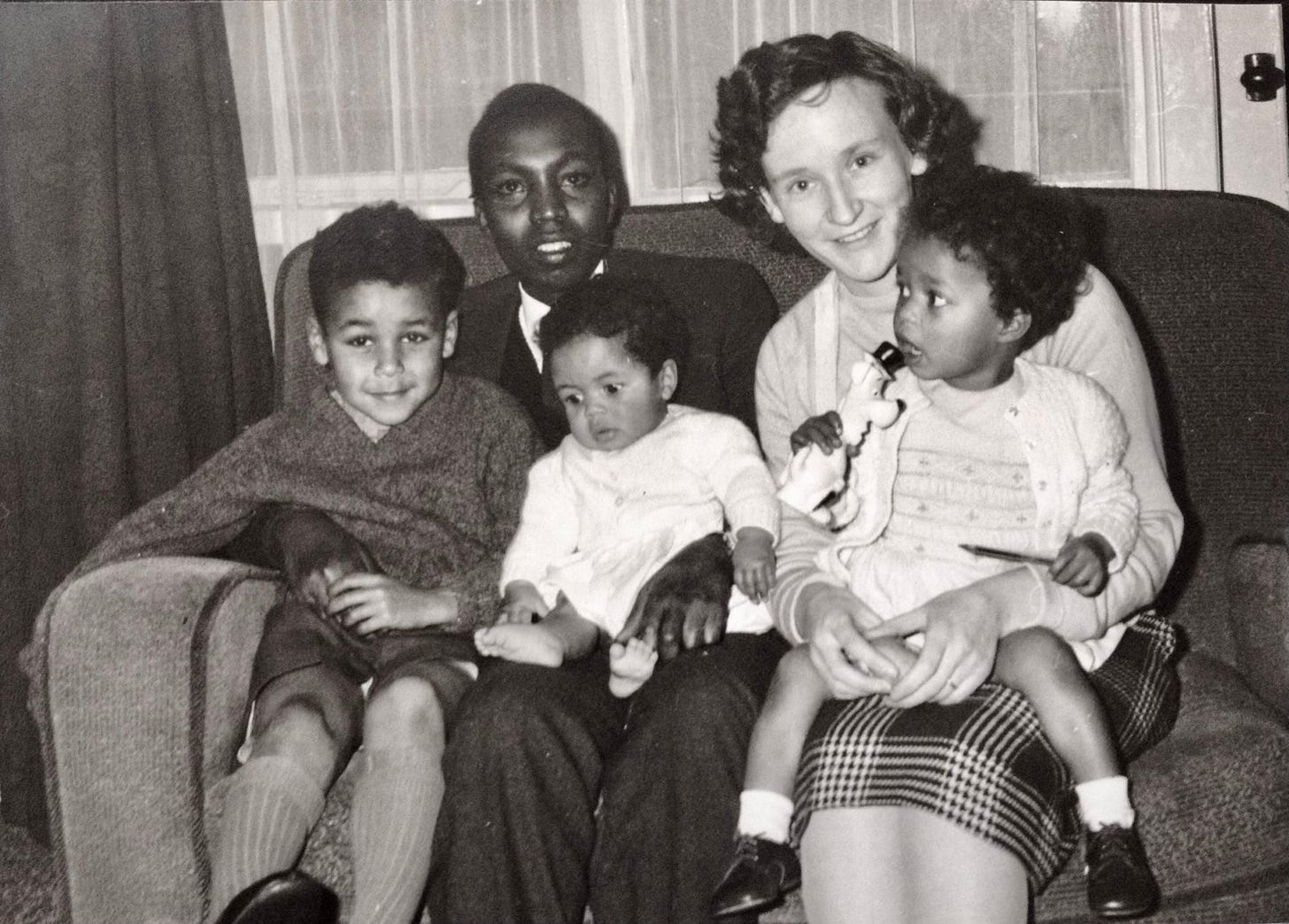

My parents met at a university dance, a formal affair with long dresses and black ties. When a foreign student approached the group of women next to my mother, one of them said, “Ugh, here comes a Black — I hope he doesn’t ask me to dance!” Mum was disgusted and when the handsome, charming ‘Black’ asked her instead, she immediately said, Yes.

When my parents married in the 1950s, my mother’s favorite aunt warned that her children would “inherit the worst characteristics of both races”. Mum and Dad searched for somewhere to set up home, among advertisements that warned, “No Blacks, No Dogs”. The public housing scheme where I was born wasn’t exactly welcoming of our mixed race family but having a doctor and a registered nurse as neighbors can be useful so there was a level of acceptance if not friendliness.

The plan was that when Dad passed his final exam to become a surgeon, we would all move to Kenya. He would take up practice as he had promised and my mother would work at the hospital as a nurse. But Dad fell ill and everything changed.

The move we eventually made was to the Scottish Highlands and it was without Dad. He had returned to Kenya with doomed hopes of recovery. Mum found herself alone with three young children in a city with doomed hopes of its own. As traditional industries closed or moved away, and racist violence continued to rise, my mother needed new options. She decided to retrain as a teacher so that her schedule would coincide with mine and my brothers’.

My mother was able to pull off working nightshifts as a nurse, a full-time teacher training course, and hold our family together with bedtime stories and picnics at the park. To complete the spectacular, against the odds, life reset, she landed a headmistress position straight out of college. The headship was for a poorly funded two-teacher school, miles off anyone’s radar, but it came with a house and it changed the trajectory of all our lives immeasurably. I am forever blessed to have grown up in a tiny Highland village, surrounded by lambing fields and good people.

So, perhaps it’s genetic, this drive to go off-road and carve a new path rather than keep trudging along the unpromising one you’re already on. My sons have continued the tradition. I might have expected them to go to college but they wanted to be outdoors, challenging themselves—mentally, physically, and socially. They both enlisted in the military after high school and now their jobs have them stationed thousands of miles away from where they grew up.

Sometimes taking the path less traveled is less a choice and more a response to a curveball. One of my kids is trans—that’s a doozy of a curveball, especially for a high school freshman.

Being a parent during that time is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. The path through it had to be both found and created, and it charted some treacherous territory. I look back now, at the transition of an anxious, depressed teen to the vibrant, hopeful soul I recognize from birth, and I remember the difficulties and uncertainties; but I also remember how ‘right’ it felt. The process never felt forced or stuck, it felt as if a benevolent unseen stream was carrying us along.

Going with the flow doesn’t always mean following a path of no resistance. Sometimes the flow is torrential, forcing you over, and under, and around rocks that make you bleed. And the flow makes no promises about delivering you into a gentle golden pond—you may be headed for a waterfall.

Sometimes, when I’m in the flow of a major life transition, it feels as if uncertainty and fear are the point—that they are the catalyst for the change I need to make. Transformations begin by dismantling old forms to make way for the new and white-knuckling through the rapids of change helps me develop the resolve I need to rebuild.

Growing Boldly

So here I am, emerging from the rapids of my latest transformation. The worst of the fear is behind me—the weeks of churning panic as I navigated decisions and uncertainty. How will I pay for my house to be unexpectedly rewired? What do I do about healthcare and medications while I’m overseas, about paying my taxes, about a legally required mailing address—about my mail-in ballot for the November election?

I have learned something unexpected about the power of fear— get too close or too far removed and paralysis sets in, but there’s a sweet spot where fear becomes a driving force. Not motivation exactly, it’s too impassive for that. It’s more like an atmospheric pressure that keeps perceptions heightened and the mind active.

I’m switching metaphors now but, go underground and a subway train hurtles along two rails toward the future; its progress depends on a third rail that carries enough power to knock the passenger dead. Fear is a third rail; it can move you forward, as long as you have adequate insulation.

Writing has been my insulation while I’ve tried to stay on track the past few months. Losing myself in an essay, or an outline for a new story—the dopamine hit of finishing a piece and hitting the ‘publish’ button. The ‘be a writer’ part of the plan has surprised me by being the easiest to accomplish.

Something else that helped is a quote I have long loved. It’s usually attributed to Goethe but it appears in a 1951 book written by the Scottish mountaineer, W. H. Murray, about an expedition to the Himalayas.1 It’s a more eloquent expression of ‘fortune favors the brave’.

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too.

All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.

Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now.

I love that; don’t just dream—Begin. Be bold and hum along with the power of the third rail and see where the tracks take you.

I am struck by how often I have taken a leap of faith and the fates have conspired to help; a last-minute vacation turns into the trip of a lifetime, an off-chance remark to a stranger leads to a business opportunity, my decision to become a writer coincides with a revolution in publishing. You might call it chance or coincidence but having a little faith that higher powers are at work has rarely steered me wrong.

None of this is to say I am entirely calm and self-assured about the next phase of my life. The big decisions have been made but only time will tell how it all plays out.

Between Decisions and Outcomes

When my son asked me how I felt about my trip, now that I was finally on my way, my mind filled with a thousand messy details I hadn’t taken care of. I thought of the mistakes I’ve made but don’t know about yet, and the consequences of choices that may be lying in wait for me somewhere down the road.

Then I remembered

, World Series Poker Champion and author of QUIT: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away, who says that many of us confuse decisions with outcomes. Ask someone about a great decision they made and they’ll tell you how they decided to buy a lottery ticket and it won the jackpot. Winning is a great outcome but buying a lottery ticket is a lousy decision—you don’t control the odds and you’re almost certain to lose.I told my son that I don’t know what the outcome of this adventure will be, but I’m satisfied that the decision to ‘blow up my life’ was a good one. I’ve done my best to tilt the odds in my favor; hopefully, my tenant will pay the rent on time and take care of my house, and dog-sitting will take me to lovely places, minimize my housing costs, and ensure I get outside for plenty of walks. There may be curveballs to come but I’m glad to be in the game.

I’m excited to get stuck into full-time writing, to explore the possibilities for the words and stories that swirl in my head and the world I inhabit. I know it will be hard work and my third rail fear is that it might not be worth it—that I might not be able to do the work well enough for it to matter to anyone, including me.

The insulation for this third rail is you—subscribers looking forward to a story on Sunday, readers who leave a comment or a heart 🩷2 , and everyone who shares my stories so that new readers can discover Whole Stories Shortly.

It takes a certain kind of boldness to take the first step, to commit to a journey when the destination is not exactly known. But I’m ready and I hope you’ll join me, after all— boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.

Let’s begin.

Readers like you subscribe to Whole Stories Shortly to follow my work as I write and travel.

Upgrade with a paid subscription to help keep the wheels turning—and you are as appreciated as a harvest of vegetables, fresh from the garden, and a favorite cookbook that promises deliciousness to come, what could be better than that?!

The quotation often attributed to Goethe is in fact by William Hutchinson Murray (1913-1996), from his 1951 book entitled The Scottish Himalayan Expedition. Learn more at ThoughtCo.com

If you’re reading this in an email, you won’t be able to comment or 🤍. You can interact with my stories, upgrade your subscription and more by downloading the Substack app or reading my work in your browser by clicking the link below.

Wow, Beth. I loved reading about your story. I'm looking forward to following along!

Thank you for this, Beth!

I can so relate to your journey, having moved around & lived in different countries a lot for the past 30+ yrs, and having chosen a non-traditional path over security and ‘fitting in’. It’s not always comfortable - but it’s also essential for my well-being.

I am looking forward to hearing more about your unfolding ❤️✨❤️😊